Advocate Viraj Patil, Co-Founder of the Law Firm, and his capable team of lawyers and paralegals at ParthaSaarathi Legal Consultancy and Dispute Resolution, Navi Mumbai, would like to provide information regarding the Uniform Civil Code in this article.

The Delhi High Court has stated that the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) should not “remain a mere aspiration,” highlighting the necessity of having a similar set of civil laws that govern marriage and divorce, among other things

“In modern Indian society, which is rapidly becoming homogeneous, the traditional barriers of religion, community, and caste are steadily dissipating,” Justice Pratibha M. Singh wrote in a July verdict.

“Indian youngsters from various communities, tribes, castes, or religions who solemnize their weddings should not be obliged to grapple with challenges originating from conflicts in numerous personal laws, notably in respect to marriage and divorce,” the court noted.

According to the advocate in Navi Mumbai, the HC was considering a plea to apply the Hindu Marriage Act 1955 to a couple from the Meena community, a declared Scheduled Tribe from Rajasthan. While Section 2(2) of the 1955 Act states that it does not apply to members of Scheduled Tribes, the court decided that it did in this case because the couple married according to Hindu rights, rites, and customs.

The HC then alluded to different Supreme Court judgments to underline the need for a “code — common to all” while analyzing the contradictions in personal laws.

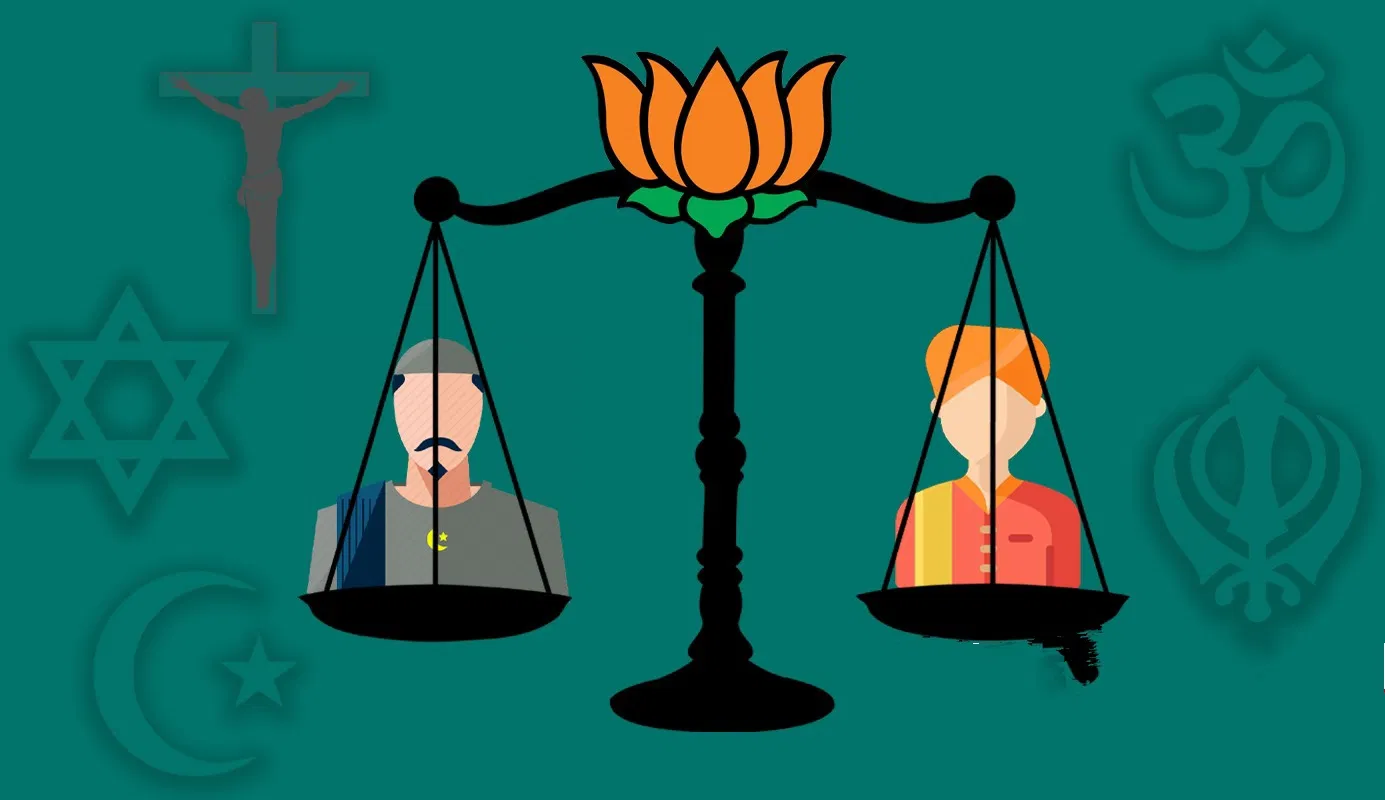

The Indian Constitution contemplates a UCC, but some contend that the concept violates religious freedom. Proponents of a UCC, on the other hand, argue that maintaining the country’s unity is critical.

“The State shall endeavor to provide for the citizens a uniform civil code across the territory of India,” reads Article 44 of the Constitution. A civil code like this envisions a standard set of civil laws for everybody in the country, regardless of religion, on issues like marriage, divorce, adoption, succession, inheritance.

This clause, however, falls under the category of state policy directive principles and is not a fundamental right.

According to Article 37, these principles are “essential in the country’s government,” and it is the State’s responsibility to apply them while enacting legislation. However, unlike fundamental rights, the courts cannot enforce directive principles, nor can persons petition the courts to have them implemented.

“A common civil code will aid national integration.”

The Supreme Court has spoken on the Uniform Civil Code several times over the years. However, these were only passing comments rather than binding orders, with the court acknowledging that enacting such a code is solely a legislative matter.

The Supreme Court, for example, expressed sorrow in 1985 that Article 44 had remained a “dead letter.” It went on to say that “a common civil code will aid the cause of national unification by removing divergent allegiance to laws with opposing philosophies” and that “it is the State’s responsibility to ensure a consistent civil code.”

By then, the issue had become highly politicized, with then-prime minister Rajiv Gandhi overturning the effect of the Supreme Court decision bypassing the Muslim Women (Protection on Divorce Act), 1986, which limited Muslim women’s maintenance to iddat, a period following the dissolution of their marriage during which they are unable to remarry.

UCC is now only available in Goa. S.A. Bobde, India’s former chief justice, praised this and encouraged “intellectuals” engaged in “academic discussion” to visit the State to learn more about it. The Supreme Court recognized it as a “shining example” of UCC in a 2019 ruling, noting that the framers of the Constitution “hoped and expected” a Uniform Civil Code for India, but that no attempt had been made to draught one.

‘Neither required nor desired.’

The Law Commission of India published a report in August 2018 stating that a Uniform Civil Code is “not necessary nor desirable at this time” in India. It further noted that “secularism cannot be incompatible with multiplicity.”

However, the researchers acknowledged that discriminatory practices existed throughout the country’s various family laws. As a result, it proposed several reforms to marriage and divorce rules applied to all religions. For example, it wants both boys and girls to be permitted to marry at the age of 18, according to Navi Mumbai’s best lawyer.

Polygamy should be deemed a criminal offense for all societies, including Muslims, according to the group. It had stated that this was not being proposed “due to solely a moral position on bigamy, or to exalt monogamy, but rather because only a male is granted numerous wives, which is unfair.”

However, the commission held off on making a recommendation on polygamy because a petition calling for a prohibition is now pending at the Supreme Court.